Entertainment

The Matchgirls Strike in ‘Enola Holmes 2’ was a real event. Here’s what happened.

Sherlock’s smart, adventurous, tough little sister is back in Enola Holmes 2 with a new case to crack. But the fictional mystery of Netflix‘s detective adventure is anchored in historical events, with a real moment of women’s and labour rights history at its core.

While Sherlock (Henry Cavill) is investigating a high-flying financial corruption case, Enola (Millie Bobby Brown) picks up a case of a missing working class woman whose disappearance might not have made it through the door of 221B Baker Street. She’s recruited by a young girl, Bessie Chapman (Serrana Su-Ling Bliss) to find her missing sister, Sarah (Hannah Dodd), who works with her at a match factory in London’s South Bank.

In director Harry Bradbeer and scribe Jack Thorne’s story, Enola’s search for clues leads her through Victorian London’s upper echelons. But more importantly, the case is steeped in a deadly conspiracy afoot in London’s brutal factories, where working class women were powerless against greedy male managers more interested in the bottom line than worker safety. It’s here that Thorne and Bradbeer introduce a historical figure into their mystery; knowing the history behind this character does comprise a bit of a spoiler, so proceed with caution.

Who was Sarah Chapman?

Sarah Chapman, the missing woman at the heart of the narrative in Enola Holmes 2, was a real person and a key organiser of the historic Matchgirls Strike at the Bryant and May match factory in Bow, London, on July 5, 1888, an action that, as the film describes it, was “the first ever industrial action taken by women for women.”

According to a piece written for the People’s History Museum by Sam Johnson, Chapman’s great granddaughter, Chapman was born in 1862 in East London’s Mile End and was working as a matchmaking machinist by the age of 19. (Johnson also cites Dr Anna Robinson’s MA thesis, Neither Hidden Nor Condescended To: Overlooking Sarah Chapman.)

Chapman was integral to both the strike and some of the first labour unions in England — she, along with Alice Francis, Mary Cummings, Kate Sclater, Mary Driscoll, Eliza Martin, Jane Wakeling, and Mary Naulls, formed the Matchgirls Strike Committee (more on the actual strike below). There’s an awesome photo of Chapman on the PHM website with the Union Committee she was later elected to, where she was one of only 10 women among 500 people to attend the International Trades Union Congress in November 1888.

What was the Matchgirls Strike?

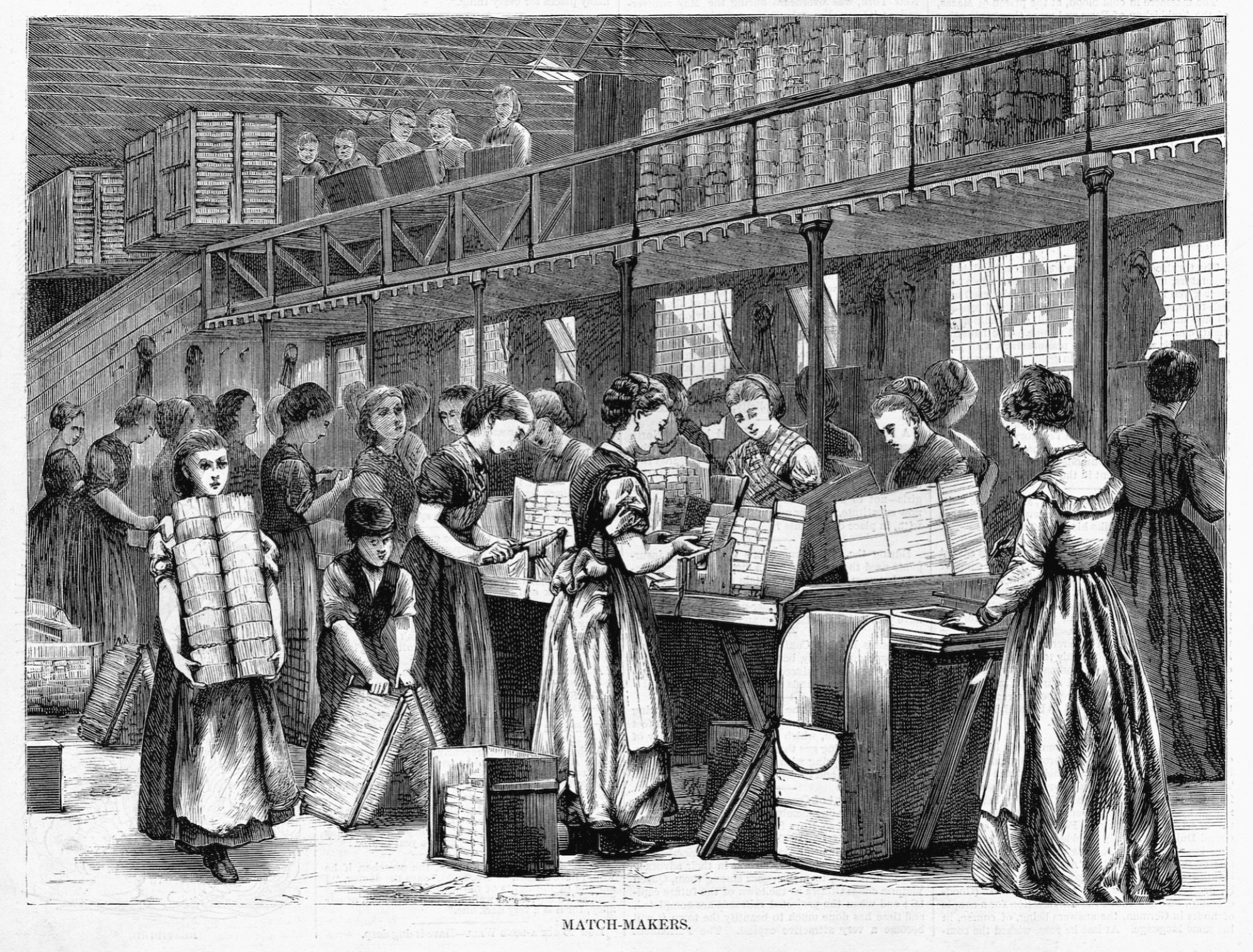

Women and girls working in the Bryant and May match factory in Bow, East London, suffered extremely poor working conditions, according to the BBC, as did many in similar factories. These included extremely long working hours and measly pay, which was further reduced due to severe fines for small offenses like lateness or using the bathroom, and having to pay for their own equipment.

An illustration of women making matches in a factory in London, England. Ca. 1871.

Credit: Corbis via Getty Images

But, as the big reveal in Enola Holmes 2 shows, the workers were also exposed to the severe health dangers of working with white phosphorus — the wooden matches were dipped in it. The most significant development was a painful form of necrosis dubbed “phossy jaw.” A character in Enola Holmes 2 is denied work due to the condition, after the foreman declares it falsely as typhus. As newspaper articles from the National Archive show, factory owners William Bryant and Francis May failed to report multiple cases of phosphorous poisoning, and even “deliberately and systematically concealed and suppress” them.

Meanwhile, Bryant and May were rolling in profits. According to The Matchgirls Memorial, a nonprofit organization raising awareness about the strike, British socialist organisation the Fabian Society held a meeting on June 15 where member Henry Hyde Champion revealed the staggering profits Bryant and May were making while their workers were on a pittance, and successfully proposed a boycott of the matches.

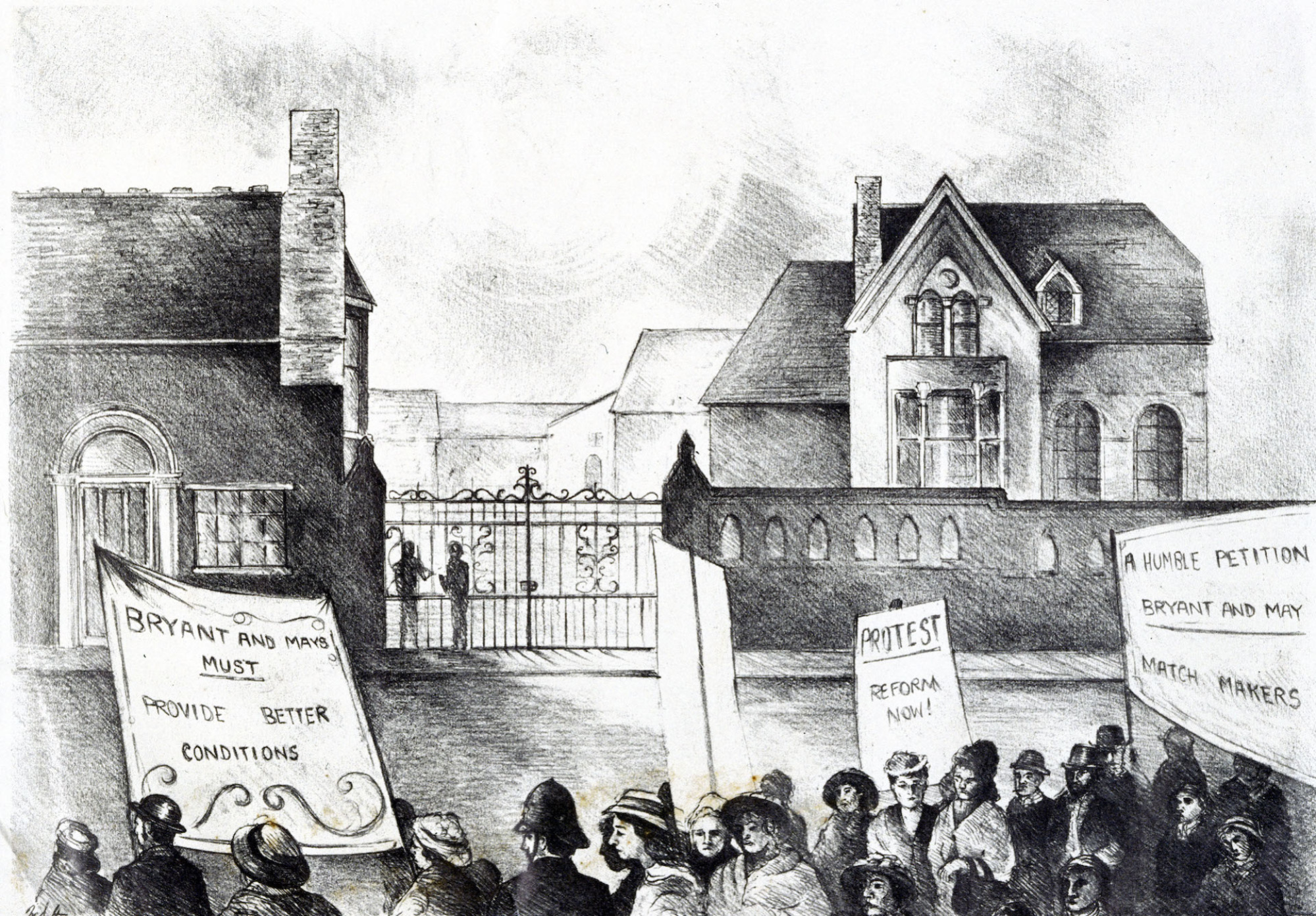

Members of the Matchmakers Union who went on strike at the Bryant and May’s factory in London.

Credit: Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Unrest had began bubbling in the factory, and women’s rights activist Annie Besant met with workers outside their workplace to hear their experiences, and published an article about the factory conditions in The Link newspaper on June 23, 1888. According to the British Library, Bryant and May tried to get workers to deny the report, a request that was refused.

But the real spark that lit the movement was when one of the workers at the factory was fired. On July 5, 1888, 1,400 women and girls walked out, protesting the dismissal and their overall treatment in the workplace.

A photomechanical reproduction of the Matchgirls Strike.

Credit: SSPL / Getty Images

What happened after the strike?

The Matchgirls Strike sparked conversation across England and contributed to the growth of the workers’ rights and union movement. At the close of the film, onscreen text says the strike “improved their working conditions forever.”

According to The Matchgirls Memorial, After the walkout around 200 women and girls marched to Annie Besant’s office, and three women — Mary Naulls, Mary Cummings, and Sarah Chapman — spoke to her about forming the aforementioned Matchgirls Strike Committee, which was founded on July 8 (three days after the strike). The event saw significant press attention, and Besant took 56 girls and women to the House of Commons to meet with MPs on July 10.

A week later, the Strike Committee and London Trades Council met with Bryant and May to agree on terms, which included among other things that all fines for workers to be abolished, all women who walked out to be rehired, the company supply of key tools like paint and brushes (which were previously supplied by the workers themselves), a meal room, and crucially, that a union should be formed. The use of white phosphorous in matches has since been banned, but it took Bryant and May over 10 years after the strike to do so, in 1901.

The action had a huge impact on the British trade union movement. In the newly formed Union of Women Matchmakers, 12 women were elected: Sarah Chapman, Alice Francis, Mary Cummings, Kate Sclater, Mary Driscoll, Eliza Martin, Jane Wakeling, and Mary Naulls from the Matchgirls Strike Committee, along with Louisa Beck, Julia Gamelton, Ellen Johnson, Eliza Price, and Jane Staines. (The union would later include men workers.) A year later, the London Dock Strike happened after the formation of a docker’s union, which saw a rise in pay for workers. The power of these actions of protest, as well as this rise in trade union movements in Britain, led to the foundation of the Labour Party in 1900.

A London Heritage blue plaque was installed at the former Bryant and May match factory on July 5, 2022, to commemorate the strike.

The blue plaque was installed in July.

Credit: Carl Court / Getty Images

Descendants of the matchgirls took a photograph together on the day.

Credit: Carl Court / Getty Images

So, there you go. When you’re watching Enola Holmes 2, remember working women like Sarah Chapman actually mustered the collective courage to walk out in protest of their abysmal working conditions and start a workers’ rights movement that would benefit people in the workplace for generations to come.

Enola Holmes 2 is now streaming on Netflix.(opens in a new tab)

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoElon Musk completes Twitter purchase, Meta’s in trouble and it’s time to admit self-driving cars ain’t gonna happen

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSPINMAZE App virus and/or malware suddenly appears on Android mobile smartphone devices #spinmaze

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days agoNASA’s about to test Martian landing gear in space thanks to this visionary

-

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days agoElon Musk, Twitter is enough. Please don’t resurrect Vine.

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoUber tests push notifications, a feature literally no one wants

-

Entertainment6 days ago

Entertainment6 days ago31 greatest breakup films to mend a shattered heart in 2022

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoBlackbird’s latest $1B AUD fund signals maturation of Australian, New Zealand venture scene

-

Entertainment4 days ago

Entertainment4 days agoWhat managers should know about quiet quitting