Entertainment

NASA detects ancient asteroids loaded with water

Scientists have identified a new type of large, dark space rock in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter that is flush with water.

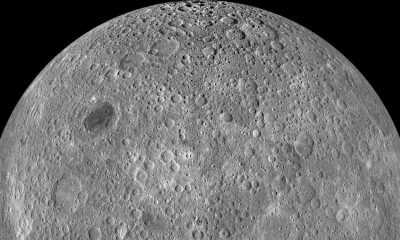

This asteroid group has striking similarities to Ceres, the only dwarf planet within the inner part of the solar system, known for being chock-full of H2O. But these asteroids — though relatively close to Ceres — are orbiting farther out in the belt than their much larger sibling.

The discovery, made with measurements taken at the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii, adds to the mounting evidence indicating asteroids in the main belt migrated there from a cold nether region, perhaps beyond the orbit of Neptune or Pluto. Such clues suggest the massive gravity of giant planets in the primitive solar system changed their travel plans, nudging the asteroids to their present location, relatively closer to the sun.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

How Earth got water

The new class of asteroids might thrill astronomers who are proponents of the theory that Earth’s oceans formed from icy comets and asteroids(Opens in a new tab) smashing into the planet. While some scientists believe primitive Earth vented out gasses 4.5 billion years ago, eventually creating an atmosphere that allowed rain to fall and pool(Opens in a new tab), many believe the large bodies of water formed because space rocks from the outer edge of the solar system brought water to it or some combination of the two. The mystery hasn’t been solved yet.

Though this group of asteroids isn’t quite a “missing link” to Earth’s hydration history, the research does back up the idea that super faraway rocks brought ingredients for water to an otherwise arid region of the solar system, said Andy Rivkin, a planetary astronomer at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab. Rivkin, who wasn’t involved in this study, is an expert on asteroids with water and organic materials.

“This would be perhaps the kind of objects that made it into the solar system and brought ice and organics with them,” Rivkin told Mashable. “Their cousins might have hit the Earth and brought some of that, as well as hitting Mars.”

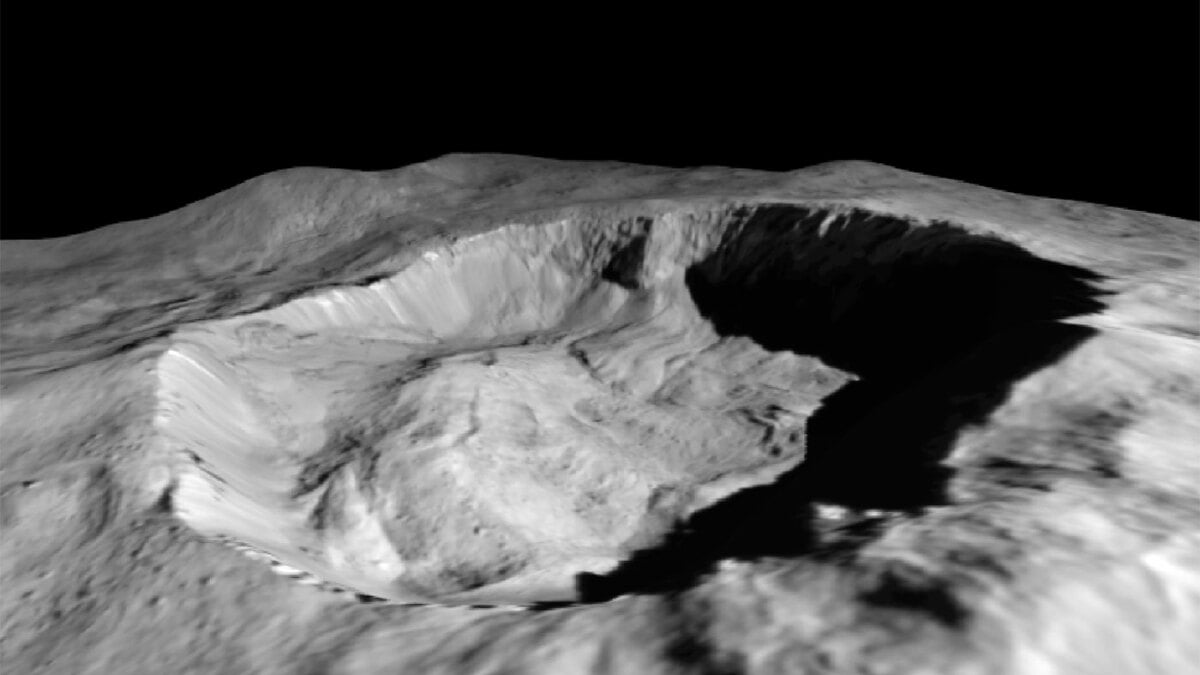

NASA’s Dawn spacecraft took these images of dwarf planet Ceres on Feb. 25, 2015.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UCLA / MPS / DLR / IDA

Millions of asteroids orbit the sun. They’re the rubble left over from the formation of the solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. Often asteroids get stereotyped as menaces of the planetary neighborhood, snatching sensational headlines for coming “close to Earth,” even when they’re safely tumbling millions of miles off in the distance. Astronomers tend to think of them as menial rocks that couldn’t quite hack it, never coalescing and amounting to an actual planet.

But their scientific value is undeniable, providing an ancient record of the complex chemical and physical changes that happened over time in the solar nebula — the gas and dust cloud from which the sun and planets formed, said Driss Takir, lead author of the study(Opens in a new tab) published in Nature Astronomy this week. The new Ceres-like class of asteroids, rich in water and carbon, possess the same ingredients essential to life on Earth.

“These asteroids can help us better understand the origin and evolution of our solar system,” he told Mashable.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

“These asteroids can help us better understand the origin and evolution of our solar system.”

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Top Stories newsletter today.

Scientists from Heidelberg University in Germany(Opens in a new tab) who collaborated on the research used computer simulations to study how these asteroids could have migrated from the outer solar system to today’s asteroid belt.

After observing 100 carbonaceous asteroids(Opens in a new tab) with infrared spectroscopy, a process of measuring the light reflected from a surface to reveal information about its minerals, Takir has detected 15 dark and water-rich asteroids like Ceres. With more observations, he believes scientists will be able to estimate just how many others like them exist in the main asteroid belt.

What Ceres is made of

As cosmic objects go, Ceres was pretty obscure before 2006, known to experts then as a huge, 500-mile-wide asteroid more than 250 million miles from the sun. At the same time the scientific community demoted Pluto from planet to dwarf planet, Ceres was being upgraded(Opens in a new tab) to dwarf planet. Then, in 2015, a NASA spacecraft got a closer look(Opens in a new tab) at the unusual bright patches visible on Ceres’ surface.

Through the Dawn mission(Opens in a new tab), scientists learned that Ceres was an ocean world. Its white spots were a salty crust of sodium carbonate, the same type of salt people use as a water softener. After looking at the mission data, scientists concluded that the salt was the residue of a vast, briny reservoir(Opens in a new tab) about 25 miles underground and hundreds of miles wide. Meteorite impacts either melted slush just below the surface or created large fractures in the dwarf planet, allowing salt water to ooze out of ice volcanoes.

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

Astrobiologists are interested in whether primitive lifeforms could exist on Ceres, the closest ocean world to Earth. The National Academies Planetary Science Decadal Survey(Opens in a new tab) recently recommended that NASA send a robotic spacecraft to land on Ceres to collect samples.

Just like Ceres, the discovered asteroids have minerals on their surfaces that derive from an interaction with liquid water. The research suggests at least some of these asteroids may also have water ice.

“Especially asteroid 10 Hygiea, the largest dark Ceres-like asteroid with a near-spherical shape,” Takir said. “We will need high-resolution spacecraft observations to search for water ice on these asteroids.”

Tweet may have been deleted

(opens in a new tab)

(Opens in a new tab)

Despite the strong case for outer solar system objects bringing water ingredients inward, the research team didn’t find any meteorite material on Earth matching the new class of asteroids. That wouldn’t seem to bode well for the theory if those objects never make the long journey to Earth.

But scientists say just because you don’t find pieces of them on the ground, doesn’t mean they’re not here.

“If you throw a snowball at Earth, it’s going to not really make it through the atmosphere because it’ll kind of heat up and melt and vaporize,” Rivkin said. “But the water would be added to the atmosphere.”

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoTikTok Shop expands its secondhand luxury fashion offering to the UK

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUnitedHealth says Change hackers stole health data on ‘substantial proportion of people in America’

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoMood.camera is an iOS app that feels like using a retro analog camera

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoTesla’s new growth plan is centered around mysterious cheaper models

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoXaira, an AI drug discovery startup, launches with a massive $1B, says it’s ‘ready’ to start developing drugs

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoTwo widow founders launch DayNew, a social platform for people dealing with grief and trauma

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days agoFurious Watcher fans are blasting it as ‘greedy’ over paid subscription service

-

Entertainment4 days ago

Entertainment4 days agoTesla’s in trouble. Is Elon Musk the problem?