Entertainment

‘Ferrari’ review: Michael Mann returns with a scattered but impactful biopic

Ferrari isn’t just Michael Mann’s first feature in eight years; it’s also the first one he’s released since turning 80. The 1950s period piece — which stars Adam Driver as Enzo Ferrari, the famed race car entrepreneur — is the clear output of an artist in the twilight of his career, equal parts self-reflective and self-assured, even if the result is far from Mann’s strongest work.

While it has the sheen of standard Hollywood biopic, from drama that’s mostly traditionally staged to Daniel Pemberton’s overt and operatic score, it bucks the birth-to-death biopic trend in order to focus on just a few months of Ferrari’s career. The details of his birth don’t matter to Mann, but death looms large over nearly every scene, coloring this period of Ferrari’s life with a sense of tragedy in the background and the foreground as the automobile maestro strives to keep both guilt and thoughts of mortality at bay.

Adam Driver shines as Enzo Ferrari.

Credit: Lorenzo Sisti

One of the more curious aspects of Ferrari has been the casting of Adam Driver, who — between this and Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci — appears to have inexplicably become Hollywood’s go-to Italian. Prior to yesterday’s trailer release, all that was available of the film was a production still in which Driver resembles Marvel’s reclusive former Marvel CEO Ike Perlmutter, a strange and mysterious energy he exudes in the role as well.

After an energetic opening montage of black and white, pre-World War II race car footage, in which a young, smiling Driver has been digitally inserted, the film takes on a more quiet and methodical tone. Set in 1957, it sees the nearly 60-year-old Ferrari waking up to the domestic bliss of his quaint countryside home with his young, beautiful girlfriend Lina (Shailene Woodley) and their 10-year-old son Piero. However, rather than luxuriating in this dreamlike setting, he sneaks away to his other home in Modena, where his wife Laura (Penélope Cruz) screens his important calls, manages the books of their business — which they built together from the ashes of the war — and, in wry fashion, threatens him with a loaded gun. This spirited introduction allows us both a peek at Laura, a woman at her wit’s end, as well as at Ferrari himself, from the awkward, lumbering gait he tries to imbue with balance and poise, to the brave face he tries to put on when confronted with mortal (albeit comedic) danger.

If there’s one thing Mann excels at with Ferrari, in a way few of his previous films have had the chance to showcase, it’s finding a deft balance between comedic and tragic tones. Very soon after Laura’s farcical threat, the film switches gears and re-introduces death as a much more real and immediate presence, both by having Ferrari visit the graves of his brother and older son, as well as by having him witness the death of one of his drivers on the racetrack — an incident which Ferrari may have indirectly had a hand in, as he’d encouraged the driver to push past his limits. This is quickly followed by a quip from Ferrari, delivered with grim comedic timing, setting the stage for an odd (yet oddly perfect) performance.

Driver’s transformation is, on one hand, uncanny in the way the costume design and practical hair and makeup appear to be seamlessly applied as if the actor’s face had been digitally grafted onto a larger, older body. However, Driver’s embodiment of Ferrari goes far beyond the physical, and certainly beyond his occasionally shaky Italian accent, which stands out further in the presence of actual Italian actors. The vast majority of scenes feature Ferrari surrounded by other people, during which he’s direct and curt, creating a sense of enormous ego and presence through his line readings alone. But during the rare moments when the camera catches him alone, whether in actual isolation or simply when his back is turned from other people, glimmers of his true self appear across his face, a questioning vulnerability that he doesn’t even reveal to his closest confidants.

Mann makes this masculine duality the movie’s dramatic backbone, and putting his faith in Driver’s dramatic chops is a decision that pays dividends. Unfortunately, it’s also perhaps the film’s only element that approaches true greatness. While its broad strokes are coherent — Ferrari must find a way to keep his business afloat while also sending his racers out into the field, making them face increasing dangers in his name — it finds itself thematically scattered at times, resulting in a plainness of both story and surrounding.

Ferrari falls short on numerous fronts.

Credit: Lorenzo Sisti

What is perhaps most disappointing about Ferrari is that it’s a film of “almosts,” falling just short of both thematic coherence and visual panache. A stunning scene set during Sunday Mass that’s cross-cut with a race nearby establishes an overt connection between the mechanical and the divine, but the film fails to follow through on this link. It features hints of religious meaning, framing Ferrari as an unforgiving, Old Testament deity, cruelly sacrificing his sons — both his actual son, who died of disease, and the numerous drivers on his team who risk their life and limb for him — but this, too, remains a mere sprinkling of symbolism without rigorous inspection into its meaning or implications.

There’s a poetry to some of its dialogue — the screenplay was written by Troy Kennedy Martin, based on the book Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine by Brock Yates — but that poetry is in service of gesturing towards ideas that never fully coalesce. For instance, when Ferrari offers his racers advice about overtaking their Maserati rivals, he drops a potent line about how two objects can’t possibly occupy the same space, and how the result in such a case is always disaster. It’s a useful anecdote about making firm, split-second decisions on the track, but it also speaks to the predicament unfolding in Ferrari’s personal life, as his wife Laura begins to discover hints of his secret life with Lina and Pierro, setting up an inevitable collision course.

However, it’s a theme that never fully comes to fruition either, despite Laura tumbling down a rabbit hole of deception, affording Cruz some brief but powerful material as a woman scorned. Woodley, on the other hand, receives no such benefit from this subplot. It certainly doesn’t help that her accent feels particularly un-placeable (and thus, doubly distracting), but the bigger problem facing most supporting characters is that they feel like extensions of a story that flounders while figuring out what to do with them.

At another point, a conversation between Ferrari and his son, about the design for a new engine, sees Ferrari arrive at a conclusion about function and form: He believes, perhaps as Mann does, that something functional exudes an inherent beauty. Ferrari is a functional film, to be sure, but it’s one whose existence feels at odds with this notion; it’s functional in a basic sense, wherein its drama is always intellectually clear, but rarely is it emotionally punctuated or magnified by the framing or lighting, save for a handful of shots of Driver turning away from people and facing the camera in uncomfortably intimate closeups. With a lesser actor at its center, it might not have even managed this much.

Where Mann’s masterpieces like Heat feature a riveting sense of atmosphere — there’s always a thickness in the air, born of his use of light, focus, and the interplay of characters and their environments — Ferrari is more of a concert of still images that feel mildly pleasurable to look at in isolation. However, while the simplicity of these images yields a film that is, for the most part, lukewarm, they are also complimented by a complex aesthetic flourish that rears its head from time to time as a reminder of what the movie is truly about at its core.

In its greatest moments, the visual language of Ferrari is deceptively simple.

Credit: Lorenzo Sisti

Ferrari is perhaps Mann’s most narratively and aesthetically straightforward film since The Insider in 1999, after which he had began experimenting with various video formats. The likes of Ali, Collateral, and Miami Vice offered a unique sense of tactility, given their now low-rent video quality. The aforementioned films, all released in the early to mid-2000s, were a far cry from the more classical staging of his 1992 historical epic The Last of the Mohicans, with which his latest work has a surprising amount in common.

At times, Erik Messerschmidt’s cinematography on Ferrari evokes the warmth that Dante Spinotti brought to Mohicans, and it even features a similar sense of Tinseltown grandeur (it had a reported price tag of $90 million) given its lush costumes, and its scenes of numerous extras lining the race tracks. However, Mann’s use of typical biopic trappings functions as something of a visual bait-and-switch. Where his last film, Blackhat, served as a chance to tinker with various frame rates and shutter angles, Ferrari is, for the most art, as traditionally “movie-like” as can be, between unobtrusive blocking aimed at basic dialogue coverage to various other technical specifics that result in a comfortably familiar look. However, early into the runtime, Mann and Messerschmidt introduce a subtle flourish of visual language — a cinematic colloquialism, if you will— wherein an otherwise bog-standard scene might suddenly be filmed with a reduced shutter angle (or rather, its digital equivalent; Ferrari was captured on the Sony VENICE 2), changing the amount of motion blur captured in a particular shot.

Most viewers unaccustomed to technical jargon will still be familiar with this effect, even if they can’t put a name to it. The reduced exposure time on the film stock or digital sensor results in a jittery effect, the kind that Steven Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kamiński popularized in Hollywood in Saving Private Ryan during the storming of Omaha Beach. In the years since, this technique has become a hallmark of Hollywood action; it’s a visual embodiment of tension, imbuing movement with a sense of unreality and unpredictability. In Ferrari, Mann briefly introduces this visual texture during otherwise ordinary scenes, starting with Ferrari visiting his son’s grave and continuing with numerous conversations about death.

Before long, its recurrence becomes a harbinger of doom and a reminder of what potentially lurks around every corner, even during unassuming moments. It transforms the mundane into something anxiety-inducing, and though it takes up only a small fraction of the 130-minute runtime, it fills certain corners of the film with unrelenting dread, like its eventual racetrack climax — during which the movie bursts to life with a stunning series of dolly zooms that further enhance the unsettling sensation.

Ferrari may not work as a story through and through, but as a film about the lingering presence of death and one man’s futile attempts to keep it at bay, it’s occasionally enrapturing.

Ferrari is now playing in theaters.

UPDATE: Dec. 21, 2023, 4:55 p.m. EST Ferrari was reviewed out of the 2023 Venice International Film Festival. The article has been republished for the movie’s theatrical debut.

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days agoSummer Movie Preview: From ‘Alien’ and ‘Furiosa’ to ‘Deadpool and Wolverine’

-

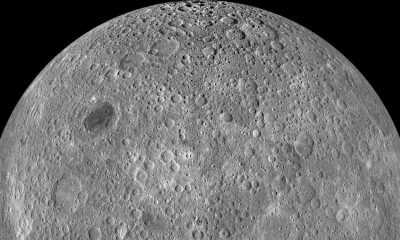

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days agoWhat’s on the far side of the moon? Not darkness.

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoThoma Bravo to take UK cybersecurity company Darktrace private in $5B deal

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHow Rubrik’s IPO paid off big for Greylock VC Asheem Chandna

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoTikTok faces a ban in the US, Tesla profits drop and healthcare data leaks

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoLondon’s first defense tech hackathon brings Ukraine war closer to the city’s startups

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoZomato’s quick commerce unit Blinkit eclipses core food business in value, says Goldman Sachs

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoPhoto-sharing community EyeEm will license users’ photos to train AI if they don’t delete them