Entertainment

‘Evil Does Not Exist’ review: Hamaguchi weaves a captivating cautionary tale

It might feel a bit obvious, the message of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s latest film Evil Does Not Exist. But nonetheless, it hits home hard.

The prolific Drive My Car director’s reputation for deeply impactful films precedes him, and his new film, which casts a sense of survivalist dread upon the natural world amid corporate development, doesn’t mince words with its warning. Evil Does Not Exist is an exciting step forward for Hamaguchi, pushing the boundaries of dramatic tension with a project a long time in the works.

What is Evil Does Not Exist about?

Credit: NEOPA, Fictive

Evil Does Not Exist tells the story of Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), who resides with his daughter, Hana (Ryo Nishikawa), in a small village outside of Tokyo, where they live in harmonious accordance with nature and its wills. But when a development plan to erect a glamping — as in glamorous camping — site near Takumi’s home is discovered by the villagers, the effects of the misguided project have negative effects on the local water supply and, in turn, wreak havoc on Takumi and his community in ways he never saw coming.

Hamaguchi’s latest film is a robust parable that questions as much as it accuses, wielding both impulses wisely. On the surface, the concept of glamping — and its truly negative effects beyond just being tacky and opulent — is definitely one of curiosity, but when you dig deeper, it becomes the perfect backdrop for the kind of lesson Hamaguchi wants to impart.

At its core, Evil Does Not Exist is a cautionary tale about the price of disrespecting nature, and it doesn’t hold back in indicting our own culpability despite our efforts. Evil does, of course, exist, especially when it comes to the disregard, disruption, and dominance of the natural world by humans.

Eiko Ishibashi’s score is to die for

Though its narrative is compelling and unique enough to intrigue, one of the most captivating elements of the film is the electrifying score by Eiko Ishibashi, with whom Hamaguchi collaborated on Drive My Car. From the film’s opening moments, music blankets the forest imagery, imbuing the scene with a grand, foreboding power. But these meticulously beautiful compositions aren’t afterthoughts, they’ve been embedded in the story and framework from the beginning through collaboration.

The film was conceived by Hamaguchi after he was approached to create visuals for one of Ishibashi’s live performances in 2021, so it’s no surprise that the compositions feel part of the intrinsic fabric of the feature film’s effective story. Hamaguchi was reportedly researching the rural village where Ishibashi grew up to create the visuals, and decided to shoot a formal feature during the process. This seamlessness and collaboration intensifies the film’s dramatic turns that much more, heightening its message of respect within the natural world.

The film’s visual language is rich and foreboding

Not only is the film a slice of auditory heaven, but it is also a visual feast. Yoshio Kitagawa’s sharp and rich cinematography is at once lush and muted, highlighting the natural beauty of the village and its surrounding areas but marring it with a wash of pallid, shadowy light. These angles work with Ishibashi’s score to amplify the film’s sense of foreboding, cementing its atmospheric tone. Kitagawa’s eye feels wholly in tune with Hamaguchi’s vision for both the beauty of the natural world and the hovering threat of evil and destruction that surrounds it.

The central performances of Evil Does Not Exist are the film’s foundation

Last, but certainly not least, Evil Does Not Exist is anchored by a set of fantastic leading performances. Omika does a wonderful job as the film’s leading patriarch, so much so that few might believe that this is his first role as an actor. He’s worked with Hamaguchi before, but in the second unit as an assistant director as well as production manager. Yet, he melts seamlessly into his part, both as a believably caring father and a steward of the natural order. It’s hard not to feel the weight of his strong performance, as well as that of Nishikawa, who plays his daughter Hana.

Credit: NEOPA, Fictive

The young Nishikawa has an almost omnipotence about her character, and she brings that same sense of instinctive ability to her performance. She tows a magically effective line as a harbinger of things to come and a being of free will at the same time, and her role in the story becomes more and more crucial as events progress. Nishikawa is certainly a young actor to watch, and her familial chemistry with Omika is what seals the film’s parabolic and important message in stone: that we must respect the world around us like our own. Rounding out the central characters, Ryuji Kosaka and Ayaka Shibutani stand out as Takahashi and Mayuzumi, representatives of the impending development and most unwelcome visitors to the village.

Evil Does Not Exist is a sobering folk tale of the power of the natural order — and what humans must do to heed it, lest we pay the price. Hamaguchi is undoubtedly back with a strong, well-earned precision in this work, unafraid to show us what we stand to lose.

Evil Does Not Exist was reviewed out of its world premiere at the 80th Venice International Film Festival; the movie hits cinemas at a later date.

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days agoSummer Movie Preview: From ‘Alien’ and ‘Furiosa’ to ‘Deadpool and Wolverine’

-

Entertainment6 days ago

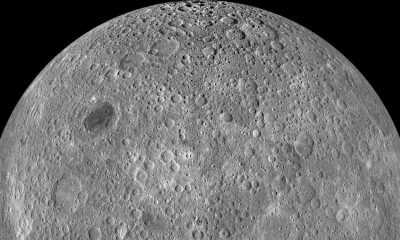

Entertainment6 days agoWhat’s on the far side of the moon? Not darkness.

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoThoma Bravo to take UK cybersecurity company Darktrace private in $5B deal

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHow Rubrik’s IPO paid off big for Greylock VC Asheem Chandna

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoTikTok faces a ban in the US, Tesla profits drop and healthcare data leaks

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoLondon’s first defense tech hackathon brings Ukraine war closer to the city’s startups

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoPhoto-sharing community EyeEm will license users’ photos to train AI if they don’t delete them

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days ago‘Challengers’ review: You’re not ready for Zendaya’s horny love-triangle drama