Entertainment

DeepWell DTx is a startup that hopes to put video games to work as real medical therapies

Play can be therapeutic. But can you dare to imagine a future where gaming is just what the doctor literally ordered?

It’s a future that DeepWell DTx is on a mission to secure. The company, which is still in its very early days, is a few things at once. It’s a development and publishing business that will build therapeutic games in-house and help its development partners do the same. It’s also, even more crucially, a regulatory services provider.

Every prescribed treatment and every over-the-counter medication in the United States is subject to regulatory approval by the Food & Drug Administration. Securing approvals is a lengthy and expensive process, but successfully navigating that process is what could turn DeepWell’s goal to deliver and set the standard for “medicinal entertainment” into reality.

“For everybody involved, what keeps bringing us all back is the purpose, the mission, and how big this could be,” DeepWell co-founder Mike Wilson said. “It’s not just about the games we make; [it’s also about] reframing people’s viewpoint on the games they already love.”

Wilson, a founding father of the irreverent indie game publishing label Devolver Digital, is teamed up here with Ryan Douglas, an accomplished inventor of medical technologies and former executive in the medtech space — two vastly different backgrounds. But it’s perhaps fitting that their idea is one born out of mutual empathy.

The business of healing

“When I met Ryan, he was grieving,” Wilson said. Douglas was in the midst of a looming exit from Nextern, the medical devices company where he’d spent 15 years as president, CEO, and co-chairman. And that massive life change unfolded as he processed a much more personal layer of grief.

“He had lost his wife after a long [health struggle] and he was in a fragile spot,” Wilson said. The two men, who were also both eyeing retirement after making their successful careers on the business side of uniquely creative fields, quickly bonded.

Wilson recalled an early conversation where he laid it all out for his future DeepWell partner: “I understand where you’re at. I’ve never lost my wife, but I’ve lost my greatest friend and I’ve lost my sister and I’ve lost my dad. If you just want to walk around and cry, I’m your guy. We don’t have to do any business together.”

It was business that brought them together initially, and unexpectedly. Wilson, who left Devolver in 2020, had designs on building an immersive art experience “completely away from digital” as his next move. Douglas, who was writing a book at the time with Wilson’s would-be partner in the new endeavor, ended up stepping in on his co-writer’s behalf for what turned out to be a momentous meeting.

“Ryan was like a last minute tag-in, which was great because he actually lived [nearby],” Wilson explained. His project ended up falling apart amid the 2020 pandemic, but he and Douglas both realized in the midst of their budding friendship that, perhaps, there was something they could build together. Douglas knows about building big businesses and navigating the federal government’s bureaucratic systems. By contrast, Wilson’s company had been a smaller and scrappier operation, but it had gained global reach, and his time there had left him with the contacts needed to open doors in the world of gaming.

“Ryan and I honestly couldn’t be more different. But what we had in common was we had come up with faster, lighter ways to navigate an industry that was increasingly bloated and stodgy and slow-moving,” Wilson said.

At first, though, Douglas needed some convincing.

Fresh idea meets stale research

‘Call of Duty: Modern Warfare II’ continues the franchise’s long history of courting controversy

“I think Mike and I were kind of uniquely suited to do this because we didn’t have to. We were both very satisfied with the outcomes of our careers and our lives. If anything, we were really just trying to settle down and play tennis,” Douglas said.

So when Wilson shared the ideas that would eventually become the foundation of DeepWell, the response from Douglas, who was looking forward to some relaxation, was skepticism. But in the end, it was the science that convinced him.

“Mike […] threw a couple studies my way, and as I dug deeper and deeper, I [was] like ‘Oh my god!'” Research is indeed promising. A review of past studies published in early 2022, looked at real and measurable benefits after the experimental use of video games as a tool for keeping patients being treated for depressive disorders engaged in and more receptive to psychotherapy. Another, conducted by Oxford University several years earlier, found that games can have positive impacts on a person’s mental well-being.

Surprised by the extent of existing research already, Douglas dug deeper and started to notice some encouraging signs for Wilson’s pitch. He saw how research had proven that games could function as a “therapeutic delivery mechanism,” for one. Personal responsibility and a desire to feel better aren’t always enough to keep patients on top of taking their medication on a schedule

It might sound silly, but Douglas knows what a challenge it can be in the healthcare world to convince patients that they need to take care of themselves. “All we do is invent stuff that could keep you alive [but] nobody will do it,” he said with a rueful chuckle. “So the therapeutic delivery grabbed me right away.”

Douglas also noticed the recurring theme of games potentially serving as a form of “adjunctive therapy,” which is an area he knows well already thanks to his work in the medical devices space. The psychotherapy study above illustrates one such example in action: Games had the effect of keeping patients more engaged.

This treatment context can also help patients better endure the impacts of certain powerful pharmaceuticals. There are all kinds of drugs used for treating grave illnesses that come with a long list of unpleasant and even dangerous side effects. But with an effective adjunctive treatment, the body becomes more receptive to the drug in question, meaning a patient can take a lower dose and still get the full effect of treatment that may be causing other, unrelated harms.

“Depending on what you ate, and depending on what you did, and depending on, like, how much sunlight you got today, you might want to take a different amount of the drug or [do it] at a different time,” Douglas said.

“Talk about Pokémon going to a whole other level. We’ve watched you the entire day and we’re telling you now is your prime time to take one fraction of this pill that you otherwise would have taken. It’ll give you all the therapeutic benefit you need and give your [body] a rest.”

Having fun with science

Douglas saw the promise in all of this, but he still wasn’t totally convinced. So he turned to his family, who are all professionally engaged with medical research in some way, for help. They collaborated on a meta study, subjecting a large body of existing research into play-as-therapy to a close examination that puts the research processes and methodologies themselves to the test.

That is where the breakthrough happened for Douglas.

“It’s not that play isn’t powerful. It’s that […] there was all this academic arrogance,” Douglas said. “It’s a very meta situation.”

Again and again, he saw examples where researchers would land on “old-fashioned” strategies for educating patients and altering their behavior up front, and then hand that off to developers with a call to “gamify this!” And that’s when Douglas finally saw where things could break down.

He’d already been surprised by the vast amount of existing, and worthwhile, research into the therapeutic benefits of play, but it was here that Douglas spotted the obvious-in-hindsight dissonance between science and art. With researchers leading the process, calls to “gamify this” predictably led to developers coming up with “secondary game mechanics” like scores, badges, levels, and social status.

“That’s not the game. That’s the cool shit,” he said. Even as the medtech expert in DeepWell’s founding duo, Douglas recognized immediately that secondary mechanics are merely the reward. They can be used to communicate and reinforce the impacts of whatever therapeutic benefit is on offer, but it’s the act of play that matters most in the context of medicinal entertainment.

“What’s missing with your Fitbit, what’s missing with your RocketMath, what’s missing with a lot of these things is that you don’t play. So you lose the engagement mechanism, but you also lose the neurochemicals [your body creates] during play that make you more likely to form a new neural pathway, and more likely to choose it as a preferential pathway.”

The games that keep us engaged and playing are the ones that are fun to actually play. So if a game that’s meant to confer therapeutic benefits isn’t fun to play, it’s not going to work as intended.

“Once I saw that, I was like ‘I recognize this. This is academic arrogance,'” Douglas said. The doctors were the “big dogs” and the game developers were doing their greatest to follow the doctors’ orders, even at the expense of their own expertise and deep understanding of play and its impacts.

“Game developers are observational scientists. And they’re data scientists,” Douglas said. There’s decades worth of institutional knowledge at this point, but even in the early days of Asteroids and Pac-Man, the greatest creators organically puzzled out strategies and techniques that could keep players invested in what they’re playing and, eventually, up their sense of investment.

Douglas, knowing all of this, immediately clocked the fault line in the “treatment-first” approach of earlier studies. He saw right away how the doctors “actually took away the treatment potential of the game” by getting in the way of creators’ creativity. The meta study didn’t just sell him on Wilson’s plan, it also became an instructive cautionary tale.

“[DeepWell has] this entire infrastructure where the doctors and the quality people and the regulatory folks and the legal — everybody’s working in service of the game developer to make sure it’s a good game.”

Teaching devs what they already know

In May, the company hosted its first annual Mental Health Game Jam, inviting teams of developers to create a game from scratch “that educates, addresses, or celebrates mental health.” The Mental Health Game Jam’s Grand Prize winner was Inner Room, a narrative adventure that wrestles with pandemic depression. The runner-up, Playdate, is a game built around breathing exercises called Bíotópico. The third place winner is Fumble, a unique language puzzle game that’s about struggles with social anxiety.

Wilson relied on his reputation in the industry to find the developers who could make these games. “I went to the [creators] that I personally knew were working on games in a […] beneficial way and looking at the industry in a progressive way as well,” he said. “It was just one conversation at a time with old friends and people I respect.”

Wilson quickly found that there wasn’t anything to pitch, really. The basic idea of creating a pipeline for therapeutic games to be formally, federally recognized as such was an instant winner among devs.

Kate Edwards, former executive director of The Global Game Jam and the Independent Game Developers Association was one of those who were easily won over. “I’m like, just stop. I’m in. I’m in,” she recalls saying to Wilson as he made the pitch. “I think for a lot of us in this industry, we already know this or we already implicitly feel [that games can have therapeutic value]. So now, this is a way to elevate the truth of it in the medium we’ve been working in for decades,” she said.

A much bigger obstacle than attracting developers is the problem of how games are viewed in the mainstream. “I don’t think we’re under any illusion that what we’re doing is completely disconnected from an overall perception of games that we know is still a bit challenging in some circles,” Edwards said. “Part of the reason why I was so excited to join this is because I do think that this is a really solid, science-based way to elevate that whole conversation.”

“I feel like the only people using the science right now are using it in nefarious ways,” Wilson said. There are so many games out there that employ predatory strategies that exploit player psychology to turn a profit. “That would be a real shame, if that was the whole story of the study of psychology in video games.”

The long road ahead

DeepWell is a child of the pandemic, and the work of building it has only just begun. The global fight against COVID-19 is thought to have eased the strain of certain bureaucratic processes at the FDA, but there’s no guarantee those changes stick for the long term.

DeepWell may still be in its early stages, but the journey the two founders have been on so far is instructive. An enormous curiosity gap exists for the general public between the basic pitch of “medicinal entertainment” and games receiving actual FDA approvals, and a path to understanding exactly how games quite literally could end up becoming something the doctor ordered is woven right into DeepWell’s compelling origin story.

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days agoSummer Movie Preview: From ‘Alien’ and ‘Furiosa’ to ‘Deadpool and Wolverine’

-

Entertainment6 days ago

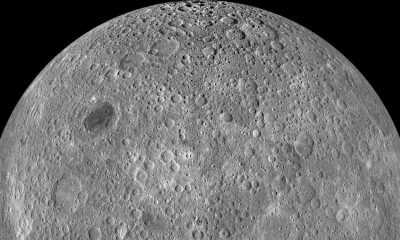

Entertainment6 days agoWhat’s on the far side of the moon? Not darkness.

-

Business7 days ago

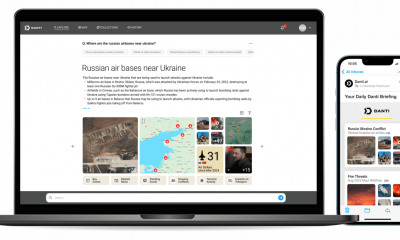

Business7 days agoThoma Bravo to take UK cybersecurity company Darktrace private in $5B deal

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHow Rubrik’s IPO paid off big for Greylock VC Asheem Chandna

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoTikTok faces a ban in the US, Tesla profits drop and healthcare data leaks

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoLondon’s first defense tech hackathon brings Ukraine war closer to the city’s startups

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoPhoto-sharing community EyeEm will license users’ photos to train AI if they don’t delete them

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days ago‘Challengers’ review: You’re not ready for Zendaya’s horny love-triangle drama