Finance

Argentina bailout by IMF — why it’s making people nervous

Protesters

hold signs with a message that reads in Spanish: “Get out IMF,”

during a demonstration against the International Monetary Fund

near the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors

meeting, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Saturday, July 21,

2018.

AP Photo/Gustavo

Garello

-

The IMF boosted its credit line to Argentina this week,

to $57.1 billion, the largest in its history. -

A larger credit line will be delivered at a faster

pace, so long as the central bank follows new

requirements. -

Some economists worry the bailout plan could cause

stagnation and political risks.

In an effort to stem a crisis has roiled Latin America’s

third-largest economy, the International Monetary

Fund this week said it would

increase Argentina’s credit line to $57.1

billion. But boosting what was already the largest

bailout in its history doesn’t come without risks, experts

say.

“While the IMF’s decision to make more credit available to the

country over the next three years has reduced sovereign default

risks over this period, things could still turn sour beyond

that,” Edward Glossop, a Latin America economist at Capital

Economics, said. “Argentina has had 22 IMF deals since 1958, and

none have restored macroeconomic stability on a sustained

basis.”

What are the changes?

- A $7.1 billion credit-line increase

- Payments will be delivered at a faster pace

- A zero-deficit target for 2019

- Restrictions on when the central bank can intervene

-

Disbursements are no longer precautionary (Argentina will

receive funding so long as it meets the conditionality of the

agreement)

Stagnation risks

New monetary-policy stipulations would minimize volatility,

analysts said, but could pose risks to economic activity. Under

the new agreement, Argentina’s central bank would only be allowed

to intervene under extreme circumstances. A “non-intervention

zone” would be set between 34 and 44 pesos per dollar beginning

in October.

“We think the main risk of this policy is to generate additional

stagnation in economic activity, particularly well into 2019,

when we expect some recovery signs to start showing,” analysts at

HSBC said. That could be especially true if

inflation, which is expected to surpass 40% this year,

remains well above target.

Meanwhile, economists are predicting the country will fall

into a recession by the end of 2018 as the government scrambles

to reduce its debt.

Gross domestic product fell sharply

between

April and June, marking the first economic contraction in more

than a year, and is expected to continue to slide in coming

quarters amid

steep spending cuts and export

tax increases.

A complicated past

Argentina has had a complicated relationship with the

IMF, which has been blamed for worsening the

country’s economic crisis in 2001. Three years after

intervention, which was followed by the largest sovereign

default in history, an independent evaluation office within the

IMF authored a 193-page report pointing

to where it may have gone wrong.

But this plan falls short of requiring a fixed exchange rate, a

factor the IMF said played “the central

role” in turning Argentina into a crisis

country. Trading one-to-one with the dollar, it provided

stability for awhile but left policymakers powerless once

investor confidence faltered.

Alberto Fernandez, who served as cabinet chief to former

President Néstor Kirchner, criticized current

President Mauricio Macri on Twitter in May when the IMF

announced plans to aid Argentina again. “The only idea that came

to Macri is to resort to the lender of last resort,” he wrote. “That

is the IMF. What a way to smash an economy.”

‘It’s about the politics’

Fiona Mackie, regional director for Latin America at The

Economist Intelligence Unit, said the new deal offers a better

plan to address inflation and normalize the economy. But she said

political uncertainty could cause turmoil in the country.

“The government should be better able to steer policy through a

difficult few months and succeed in its adjustment package,” she

said. “All that said, risks abound, and at this point it’s about

the politics, and the political capacity to keep the moderate

opposition, and voters at large, on side.”

Sticking to IMF targets may prove difficult for Macri, a

conservative whose campaign focused on free-market reforms, as

the October 2019 presidential election approaches. With an

approval rating that his dipped below 40% this year, he could

risk losing re-election.

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoLangdock raises $3M with General Catalyst to help businesses avoid vendor lock-in with LLMs

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days agoWhat Robert Durst did: Everything to know ahead of ‘The Jinx: Part 2’

-

Entertainment5 days ago

Entertainment5 days agoThis nova is on the verge of exploding. You could see it any day now.

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIndia’s election overshadowed by the rise of online misinformation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoThis camera trades pictures for AI poetry

-

Business5 days ago

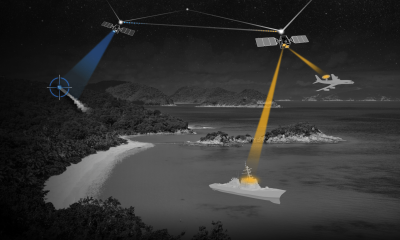

Business5 days agoCesiumAstro claims former exec spilled trade secrets to upstart competitor AnySignal

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days agoDating culture has become selfish. How do we fix it?

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoScreen Skinz raises $1.5 million seed to create custom screen protectors